Dancers are tasked with turning the sounds they hear into visual movements. For the social dancer, who must also navigate the space, remember their steps, and provide a comfortable embrace, interpreting the music can be a daunting task. At the same time, dancing musically is a wonderful, ever-changing puzzle and capturing the music through movement is a source of eternal joy. Few things in life are more enjoyable than the feeling of ‘really capturing’ the music together with your partner.

So how do we go about dancing musically? Experience (read; go to the milonga every week for years) provides a natural basis of feeling to understand what comes next in the music. This ‘natural approach’ allows us to reach a level sufficient for milongas and marathons, but in the end is limiting. Relying on our natural feelings constrains us to interpret what we naturally feel, which leads us to always dance the same song the same way. The natural approach often misses subtler aspects of the music and struggles with complex music and songs we haven’t heard before. We can always ignore our limited musical understanding and continue dancing only to the most explicit components of the same simpler “danceable” songs. Or we can take the time to analyze the structure of the music to develop a more comprehensive and sophisticated palette, allowing us to hear and feel more of the music and open new possibilities in the dance. This series of essays are for the dancer who is interested in taking this second path.

A little bit of analysis unlocks some powerful tools for interpretation. Understanding the underlying structures and conventions of the music lets us know when changes in the music will occur. Knowing the standard conventions also highlights the choices made to change these conventions, exposing the unique aspects of each song. Music analysis does not replace the natural approach, but rather supplements it. We hear what we are primed to hear and feel what we have words to describe, so our study ahead of time heightens our awareness in the moment.

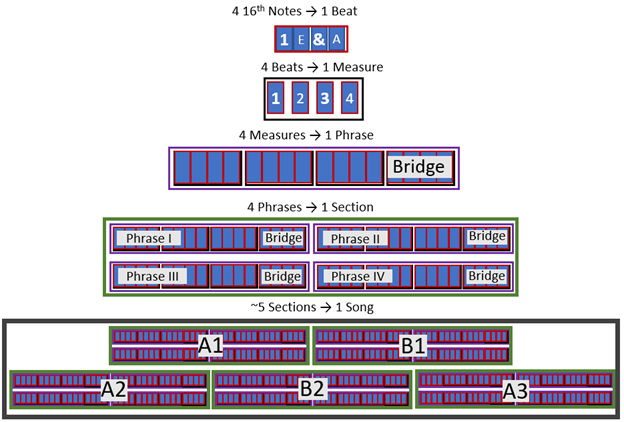

The pulse of the music is called a beat and determines the basic unit of time. Beats are broken up into four 16th notes (counted 1 E & A). For reference, 16th notes are often what the bandoneon players play during the quick ‘variation’ at the end of the song. Stepping on the beat means we are stepping on the number, and stepping on the syncopation refers to stepping on the ‘&’. We don’t tend to step on the ‘E’ and ‘A’, though we may synchronize other movements to them.

In tango, sets of four beats comprise a measure (in vals, a measure consists of three beats). We sometimes call beats 1 and 3 of the measure the downbeats, and call beats 2 and 4 the offbeats. Dancers also sometimes refer to ‘single time’ as stepping on beats 1 and 3 and ‘double time’ as stepping on all four beats of the measure, though my musician friend Heyni Solera pointed out to me that this is incorrect terminology because the musical timing has remained constant, and it is simply the speed at which we step that changes.

If we default to stepping on the 1 and 3 beats, then the ‘&’ syncopation is four times faster than our normal steps. It is important to understand syncopations to dancing to more complex music, and it is essential to understand if we want to add embellishments (doing embellishments on the syncopations allows us to sneak them in between the beats and not disturb our partner. They also tend to look better). It is well worth the effort to develop the skill to be able to step on each of the syncopated beats.

Four measures link together to form a phrase, which act as the sentences of the song. Phrases are integral to our musicality as a dancer. Starting our sequences at the start of the phrase, ending at the end of the phrase, and maintaining the same thread throughout the phrase, give structure to our dance. Otherwise, it is as if we are just speaking with a long run-on sentence. The last measure of the phrase sounds different than the other measures and is used to bridge one phrase to the next. While the structure of four measures per phrase is the most common, it is by no means a rule. Instead of trying to count the measures, listen for the bridge. It will tell us when the end of the phrase is coming and will guide us when the number of beats or measures in the phrase differs.

I need to mention that dancers often count something in between the beats and the measure, counting on beats 1 and 3. This then gives 8 counts per phrase. Dancers also used the same 8 numbers to name the movements of the basic 8 sequence, and of course we named the basic pivot movements eights (ocho). We are thus in the situation where we could lead an 8 (ocho) from the 5 (cross) on 4 (count), which is 3 (beat) of 2 (measure) of 1 (phrase). And we wonder why tango dancers get confused.

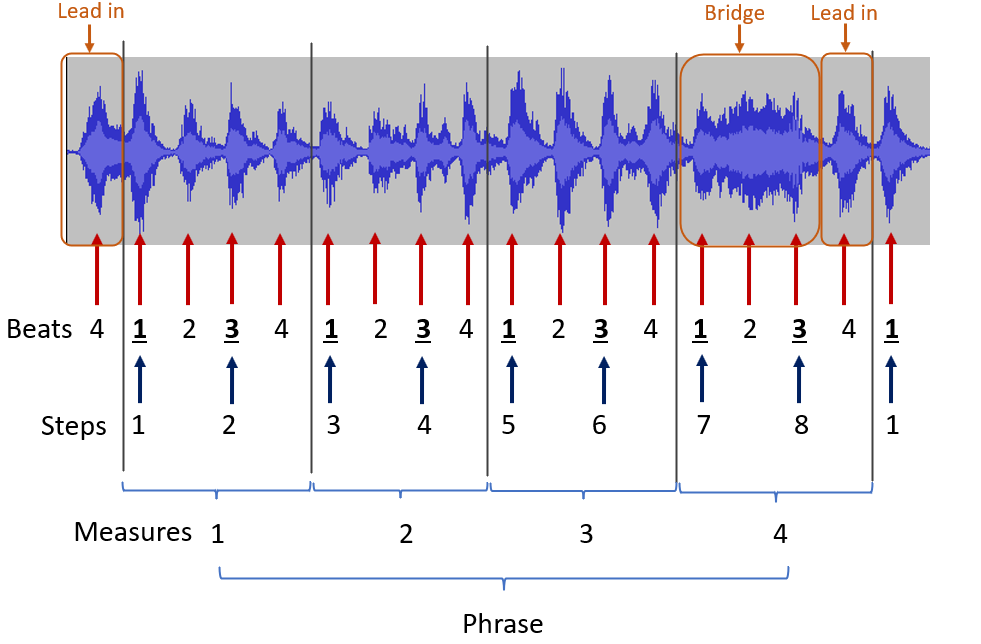

The figure on the right shows a visualization of the waveform of the first phrase of the song Ciego, by Francisco Canaro (it may be helpful to pull up the song as a reference). The peaks in amplitude show the beats. The song starts with a lead-in, meaning the very first beat is one before the measure starts. The cluster of waves in the final measure is the piano playing the bridge to signal the end of the phrase, with a lead-in to the next phrase.

Groups of four phrases form a musical section, which act as the chapters of the song. The underlying themes of the music change by section, and our dance should reflect this. The first section sets the theme A of the song. The second section is the variation and sets theme B of the song. The third section returns to theme A, the fourth section either returns to the same variation or takes a new theme C, and the final section usually returns to theme A. Songs will deviate from this basic structure, the standard strucuture is still good to know.

Here is one simple but powerful approach to musicality. Pause on each bridge and pick a ‘thread’ to dance to in the next phrase. Threads could be any choice you make: dance to a specific instrument. Dance small or big. Make your movements heavy or light. Dance linearly or circularly. Dance to the melody, countermelody, or rhythmic base. Do simple steps in close embrace or big steps in open embrace. It is not important what thread you pick. What is important is that you maintain the thread throughout the phrase and don’t get distracted by shiny objects in the music. Make a change each phrase and keep that change constant throughought the prhase. Even better if you make a change to signal when the new sections of the music occur. Of course this is just one of many approaches to musicality. Understand the musical structure and then play with it.

A final note is that musicality cannot be divorced from other parts of the dance. Dancing to syncopations is technically challenging for both leaders and followers. Capturing the beats, measures, phrases, and sections requires control of your own body, clear communication with your partner, an understanding of the vocabulary and movement possibilities, and the technical capability to express your ideas. Musicality also helps with our technique. As leaders, having a clear understanding of the music helps clarify our lead. As followers, understanding the music helps us prepare ourselves to better respond, and knowing musical structure provides the openings for a two-way conversation. Use the music as inspiration to develop these other aspects of your dance, and use these other aspects to further your musicality.