I have been recently going through the process of structuring my tango library as part of learning to DJ. While working through the orchestras, I became curious about what I thought would be a straightforward question. ‘How many tango recordings are there?’ What I thought would be a simple google search whose answer would fill a quick page turned into a couple month journey into the history of tango music, the history of the recording industry, and the history of Argentina and the world. Luckily, this rabbit hole I fell down is filled with Chessire Cats, Mad Hatters, and interesting adventures which I have tried my best to convey here.

The following sections turned out to be much longer than originally planned, though is still much shorter than each of the stories deserve. In each section, I try to answer a question that came up during my attempt to answer the original question. In total, it tells a story about the songs we listen to and dance to each night at the milonga.

What is the First Tango?

If there are a total number of tangos, then there has to be a first. But tango music evolved organically from many influences, so there is no clear cutoff where we can say before is not tango and after is tango. A question we can try to definitively answer, though, is “what is the first tango recording that we can listen to today?”

he oldest surviving recording of any song is this banger 😉 recorded in 1860 by Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville, using a phonautograph to transcribe audio onto paper.

It took a little while for the song to become a hit, with researchers at Berkeley using optical imaging to fist play it back in 2008 [1].

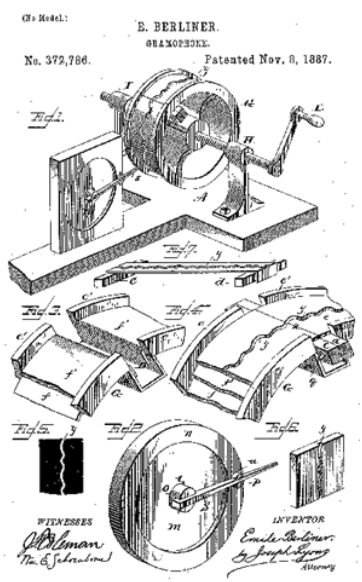

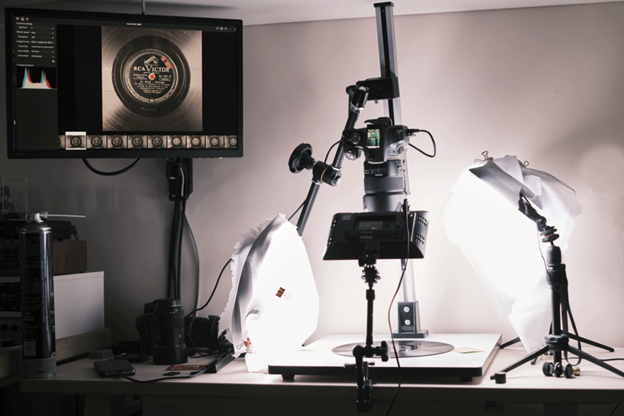

Therefore, real birth year of audio recording is with Thomas Edison’s invention of the Phonograph in 1877. Sounds were engraved onto a tinfoil (and later wax) cylinder which could then be played back. Ten years later, in 1887, Emile Berliner patented the Gramophone which allowed for the much more practical recording onto flat disks. While Berliner’s original company did not pan out, his patent rights got passed on to his partner Eldridge Johnson who founded the Consolidated Talking Machine Company, which in 1901 changed its name to the Victor Talking Machine Company [2]. Victor and RCA, the radio and electronics company Victor merged with in 1929, produced more tango records than any other label. If you ever see an old tango record, or if you use a program such as Virtual DJ which displays the record label, then you are certain to see the Victor and RCA logos.

As far I can tell, none of the few phonograph cylinders whose sounds have been digitized contain tango songs [3]. And many of the earliest recorded disks have been lost to time. The oldest surviving tango recordings may be held by the TangoVia Buenos Aires project, started by the renowned tango bassist Ignacio Varchausky, which states they have a tango recording from 1902 [4][5]. It did not seem that this recording had been digitized and made available, however.

After a fair amount of searching, the oldest recording of a tango song that I could find available online to listen to is this 1905 recording of El Choclo by the Victor Argentine Orchestra.

So, How Many Tango Recordings Are There?

Websites such as Tango-DJ.at, Tango Time Travel, Tango.Info, and El Recodo Tango provide a number of tango artist discographies. To estimate the number of tango recordings I used tango songs from the El Recodo tango collection because their data were convenient to process did not have too many duplicates. The first recordings in this list were from 1912 and the final were from 2024.

Golden age artists appear to have a close to complete representation in the dataset, but more recent tango artists were under-represented. I therefore used a cutoff date for the analysis to consider ‘historical’ tango songs. The cutoff that seems most appropriate is 1995, when the analog era of recording ended in Argentina. After cleaning the data and dropping duplicate entries, the data set includes 11,839 available tango songs recorded between 1912 to 1995. Given additional songs before 1912 along with missing entries, we can give a rough estimate of there being approximately 12 thousand historical tango recordings. This tracks El Recodo’s own estimates of the number of tango records[6]. Adding an additional 700 Milongas and 1330 Valses brings the total list to around 14 thousand songs.

When Were They Recorded?

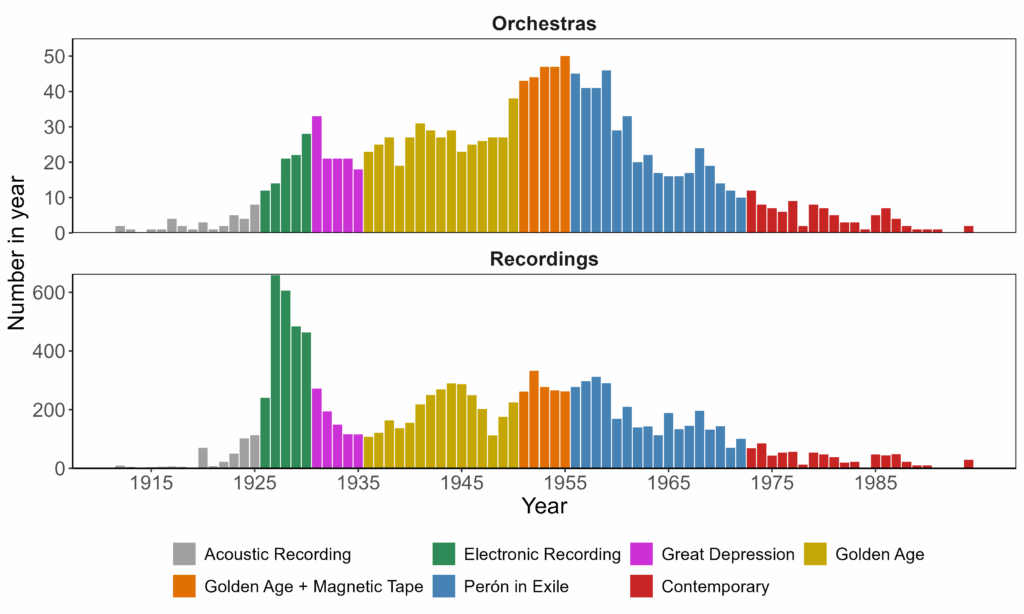

The figure above displays the number of tango orchestras and recorded tangos each year. Early audio recordings used the acoustic energy of the sound itself to power the stylus to record the sound on wax disk (The video on the right provides a good description of the acoustic recording process and the transition to electronic recording techniques).

While acoustic recording methods became quite sophisticated, the technology was limited in what sounds could be captured. Soft sounds, low frequencies, and high frequencies would all be lost in the recording process. Modern audio files generally have a frequency range of 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz and early electronic recordings had a frequency range of approximately 50 Hz to 6,000 Hz. Acoustic recordings, meanwhile, only had a range of 200 to 2,400 Hz [7].

In the early 1920’s researchers Henry Harrison and Joseph Maxfield at Bell Labs developed electrical microphones, amplifiers and electromechanical recorders which greatly improved the process of recording sound (You can read about the process in their own words here). In February 1925 Art Gillham and His Southland Syncopators recorded You May Be Lonesome, the first electrically recorded song. One year later, March 1st, 1926, electrical recording made its way to Argentina with Rosita Quiroga’s La Musa Mistonga.

Interestingly, the studios slow-rolled the new technology into Argentina with minimal marketing or fanfare to not be stuck with a large stockpile of now inferior quality acoustic records. For example, instead of the usual publicity that would follow such an improvement, the only change Victor made to denote that a new record was recorded electrically was to add a VE to denote Victor Electrical [8].

Listen to Julio de Caro’s 1925 acoustical recording of Alma De Bohemio and compare with his electrically recorded Fuiste just one year later. His 1928 recording of Ojos Brujos further shows how much the recording technology improved in just a few short years. But to get the full scope of the change in sound quality from the start of tango recordings to the start of Tango’s Golden Age, listen to the difference between Carlos Gardel’s 1912 La Mariposa, and Gardel’s Volver recorded March of 1935; just three months before his death on June 24th.

Because of the lower audio quality of acoustic recordings, the music we hear at the milonga is all from 1926 onward.

What is That Big Spike in the 1920’s?

What stands out most in the figure of recordings by year is the spike in songs from 1927-1930. What happened?

At the same time electrical microphones were revolutionizing the recording industry, advances in radio technology were revolutionizing the ability to transmit and receive signals [9]. Radio allowed an artist to reach millions of homes at once, enabling international superstars to emerge. Radio was also the OG streaming service, allowing people to listen to music without having to buy records. Facing declining sales, the record companies looked to expand their offerings to reach new audiences [10]. Add to this the post-war prosperity that marked the roaring 20’s.

The 20’s were ripe for big changes in music. To draw corollaries to music in the US at the time: Blind Lemon Jeffries recorded Matchbox Blues March 1927; Duke Ellington recorded East St. Louis Toodle-Oo, his first record to reach the charts, March 1927; The Carter Family recorded their first tracks August, 1927; Jimmy Rogers recorded his first tracks August, 1927; and Louis Armstrong recorded West End Blues June 1928. The foundations of Blues, American Folk, Country, and Jazz were all set in a few short years in the latter half of the 1920s.

Facing near-insatiable demand for music from records and radio stations, composer and band leader Francisco Canaro said, ‘hold my mate’. Canaro recorded 372 songs (325 tangos) in 1927, 344 songs (293 tangos) in 1928, 421 songs (275 tangos) in 1929, and 421 songs (221 tangos) in 1930 [11]. This is more than a song a day consistently for four years! His band recorded 16 songs in one particularly prolific session on December 12th, 1930. A significant fraction of the spike in the late 1920’s in tango recordings can be attributed to Canaro’s productivity during this period.

Who Recorded the Most?

| Artist | Tangos Recorded | First Recording | Final Recording | Recording Lifespan |

| Francisco Canaro | 1,584 | 1915 | 1973 | 58 |

| Juan D’Arienzo | 824 | 1928 | 1975 | 47 |

| Carlos Gardel | 603 | 1912 | 1935 | 23 |

| Osvaldo Fresedo | 503 | 1926 | 1980 | 54 |

| Osvaldo Pugliese | 427 | 1943 | 1986 | 43 |

| Francisco Lomuto | 399 | 1925 | 1950 | 25 |

| Aníbal Troilo | 384 | 1938 | 1971 | 33 |

| Roberto Firpo | 384 | 1917 | 1944 | 27 |

| Alfredo De Angelis | 364 | 1943 | 1985 | 42 |

| Carlos Di Sarli | 356 | 1928 | 1960 | 32 |

The table above shows the ten orchestras who recorded the most songs. In total, the top ten account for about half of all of the tango recordings. While volume is not necessarily an indicator of influence or quality, this list is a decent place to start for anyone newer to tango who wants to know who to start listening to. Unsurprisingly, Canaro was the most prolific, accounting for 13% of all tangos recorded, but the other artists on the list were no slouches either. The ‘King of the Beat’, Juan D’Arienzo comes in a strong second. And given his orchestra’s proclivity for faster tempos and ending variations, he likely comes fairly close to Canaro on a ‘total recorded notes’ basis.

What are the Most Recorded Songs?

There are a few tango classics that get recorded and played repeatedly throughout the decades. As a tango dancer, becoming familiar with these tango evergreens can go a long way to improving your musicality. The table below provides 25 of the most recorded tango songs along with selected examples for each. I choose examples that would highlight a range of tango artists and eras along with providing examples of how individual artists evolved their style throughout the years (You can also listen to them on this Spotify playlist).

In terms of number of recordings, the winner by a mile (winner by 1.6 kilometers in Argentina) is La Cumparsita. First recorded by Roberto Firpo in 1917, La Cumparsita has gone on to become the most recognized and recorded tango. A story shared to me by my friend Ragnar is that one of D’Arienzo’s versions of La Cumparsita became such a hit that audiences wouldn’t let the band leave until they played it. Hence the tradition of ending the night with La Cumparsita.

While the milonga may end with La Cumparsita, D’Arienzo tried to ensure record sales from this hit never would. His orchestra recorded no less than seven versions of the song, the first in 1928 and the final in 1971, selling more than 14 million copies of the song in total[12]. These varying versions provide an insightful timeline into how tango music evolved throughout the decades. You can hear similar differences in D’Arienzo’s Don Juan from 1936 and 1950, or Di Sarli’s 1945 and 1954 versions of A La Gran Muñeca. The various versions of El Once by Osvaldo Fresedo provide an especially vivid timeline, with recordings in 1927, ’31, ’35, ’45, ’53, and ’71.

In general, what I will call the ‘size’ of the song tended to increase over time. ‘Size’ of song is not a musical term (discussing things like composition, volume, tempo changes, and dynamic range would be more accurate), but it is certainly something we feel as dancers. Some songs naturally ask for bigger steps, more complex movements, and more changes in dynamics than others. I believe this is part of why so many dancers prefer dancing to tangos from the 1930s and ‘40s. In this period, the songs are ‘big enough’ to call for interesting movements and maintain interest for a full night, but also ‘small enough’ to fit into a crowded milonga and not tire yourself out after just a few tandas. It is also interesting that the upper end of eras for milongas is the lower end for stage performances. Most songs in the milonga are from the 30’s to early 50’s, whereas songs chosen for tango stage performances are often from the mid 50’s onwards.

How Come Many DJs have More Than 12 thousand Tango Records?

I said the estimated number of tango recordings before 1995 is around 12,000 (14,000 if we include Vals and Milonga). But I know a few DJs and music collectors whose personal libraries have 50 thousand recordings or more. And the Tango-DJ.AT states that they have data on 105,000 tango recordings![13] How can I tell you there are 12 thousand tangos when I personally know of people with tango libraries five times that size? There is a story worth telling here.

The story I am about to tell could have been taken straight from the script for a Marvel movie. It has it all—secret Nazi technology, a millionaire media icon and entrepreneur, shady corporations, political machinations, and an eclectic group of superheroes banding together to save the day.

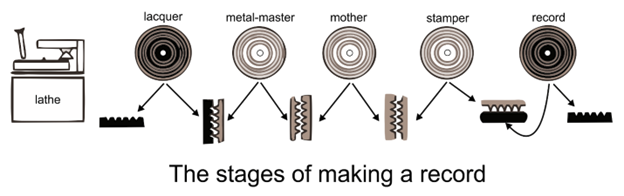

By the beginning of tango’s golden age, recording technology had already started to become dated. Recordings were lathed directly onto a lacquer disk, meaning you had one take to get the recording right with no way to edit. The actual records were made from shellac, which is a resin secreted from the Lac bug. As you can see in this video, the whole process was complex, expensive, and required a lot of expertise and equipment (if you are like me and have a strange curiosity for old-timey industrial processes, then the video is pure gold).

Note: for vinyl records, the mother-master is called a mould.

As incredible as it is that millions of people were able to enjoy recorded music for decades because of resin from a small bug, shellac is not the ideal material for audio. Shellac records are relatively big, 10-12 inches in diameter, brittle, you drop one and it shatters, and the grooves could not be cut too fine so each shellac could only hold one song per side. They are also expensive to produce, transport, and store, and the sound quality degrades with each play.

Companies were hard at work researching technology for recording and storing sound when World War II broke out. While the war put much of the research on hold, Allied signal operators started hearing something strange coming out of Germany. Things like radio broadcasts of Hitler from two places at the same time, or symphony orchestras playing from concert halls that had already been destroyed in bombing raids. The broadcasts had to be recordings but sounded as if they were live and were much longer than could be stored on Shellac. Here you can hear the superb sound quality compared to other 1944 recordings. In fact, the sound quality is so high in fact that you can actually hear the sound of the allied bombing in the background during the quieter moments (listen starting around 5:30).

Audio from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EY7lvuVjjX4

As the war was coming to an end, US Signal Corps officer Jack Mullin went on a quest to discover the new Nazi recording technology. What he finally found was high-fidelity ‘Magnetophon’ tape recorders. Mullen had one a few of these devices along with 50 reels of tape shipped back to his home in San Francisco and began working on them over the next two years[14].

Once Mullen felt he had mastered the technology, he went out looking for investors. Luckily for Mullen, Harry Lillis “Bing” Crosby Jr. was fed up with his work. Radio shows would do two live broadcasts three hours apart, one each for the East Coast and West Coast audiences.

With this schedule, Crosby was working himself ragged and missing a lot of dinners with his family. He also couldn’t go back and fix errors or take out sections before the broadcast was sent out.

When he heard about Mullen’s recording tape he immediately scheduled a meeting. Crosby invested $50k (about $500k in today’s dollars) in the Ampex company to work with Mullen to make the Reel-to-Reel tape recorder. By 1948 Bing was recording and editing his show on magnetic tape.

Around the same time as magnetic tape, record companies began coming out with new vinyl records. These were cheaper, sturdier, could hold higher fidelity, and could hold more music for the same amount of space. This 1954 video, made by the RCA company, shows the process of recording and producing vinyl. Given what occurs 10 years later, it also has the unfortunate quote “The original tape goes into the vault for safe keeping, to take its place forever alongside many other priceless performances by the world’s greatest artists.”

Magnetic tape and vinyl opened a new world of economic opportunities. Costs and production capacity are based on the number disks produced, so vinyl storing 3-6 times the number of songs per disk means production and transport costs are reduced and production capacity of songs are increased. Magnetic tape meant that a song could be recorded in a separate location from where the lacquer master was cut.

Newer record labels could record onto tape and then have the tape shipped off to a separate facility to be turned into vinyl, increasing the number of record labels recording tango in the 50s. In 1951, the first tangos recorded with tape and vinyl were by Carlos Di Sarli in 1951 with the new recording company Music-Hall [15]. Many of my personal favorite tango recordings are from the 50s—those crystal-clear songs DJs play later in the milonga were you fall in love with your partner by the end of the tanda.

The party started coming to an end with the exile of Perón by military coup in 1955. While coups were standard operating procedure for Argentina, which had 6 between 1930 and 1983, this coup was especially disruptive. The new military regime banned and censored tangos they deemed too close to “peronismo” and imprisoned a number of artists who were seen as supportive of the previous regime [16]. They prohibited gatherings in the street of three or more people and imposed a mandatory curfew. They cracked down especially hard on milongas compared to other dance venues and nightclubs. While tango music continued strong, the decimation of dance venues severed the ties between the music and the dance. By the 1960’s, both the number of tango dancers and the number of tango orchestras were in steep decline.

The 60’s dealt another devastating blow to tango. Public tastes were shifting towards a new wave of music, and record companies were facing increasing competition. A number of independent labels such as Music-Hall, who recorded the first vinyl in Argentina, had already gone bankrupt, spreading their original masters and collections to the wind. For the remaining companies, all of those old metal-masters from the shellac era were taking up a lot of space and storage costs. They were also starting to look pretty dated. After all, people weren’t making or buying shellac now that there was vinyl, so the recordings would have to be transferred anyways if they ever were to be reproduced.

In 1964, the Argentina branch of RCA decided to clear out its old warehouse of metal masters to create space for new business opportunities. It set up to transfer the masters to metal tape before destroying the old masters, but this transfer process was done in a haphazard manner. Only a portion of the masters were transferred and many of these done with limited quality control [17]. The same happened to a lessor extent with the other record labels resulting in many of the original tango masters being lost forever.

Lest you think this is tragedy confined to tango, an equally wholesale destruction of cultural heritage occurred by RCA around the same time less than an hour drive from my home. In the early 1960s, RCA deemed that its Camden New Jersey warehouse, which stored more than 300,000 disks of Victor recordings made from 1900 to 1945, would best serve the company by being dynamited to allow the rubble to be pushed into the waterfront to build a shipping dock on top of [18]. Most of the blues and jazz masters, classical recordings from the greats like Rachmaninoff [19], and recordings from artists such as Elvis Presley [20] all went up in smoke. Before the destruction, employees and a few collectors were allowed to go through the collection and take what they could carry. This must have been a surreal experience to have nearly 50 years of musical heritage in front of you and can only save what fits in your bag.

The advent of compact discs in the 1980’s, along with renewed interest in tango dancing, brought a growing interest in golden age tango recordings. The new CD format made it much more convenient to ship collections of music to customers all around the world. But what to do now that many of the original recordings were destroyed? Some of the songs had already been released as LP compilations in the 60’s but were often sped up and had reverb and echo added. When no master remained and no LP existed, employees went out to collect old records to serve as the new master [21]. The sound quality from these derivations “range from very good to poor, depending on the quality of the sources, dedication and technical competence” [22]. When transferring the old 78s to CCDs, the old records were sometimes played at the incorrect speed, changing the tempo and pitch of the song. This article provides an especially clear example of the difference tempo change. Even with the renewed interest in tango music, much of the tango discography was in a sorry state.

This is where the heroes of our story come in. A small group of collectors maintained records in good condition, and another small group went about properly restoring and remastering. The tango world is both big and small—big in that you can go pretty much anywhere and find people dancing it; small in that there are only so many of us, so anywhere you go you run into some of the same people. The effort to restore tango music was no different. The people doing this work are spread around the world, but the total number is only a few dozen.

Restoring tango recordings is detailed and painstaking work involving numerous steps to collect, prepare, digitize, and process each individual track. Those interested can read more about the whole process here, here, and here. The result of all this labor, though, is that, through websites such as Tango Time Travel and Tango Tunes, milongas and festivals now get to play the tango greats as they were meant to be heard.

This restoration work means there are now often several versions of the same recording. Each version may have used different records for the transfer and different methods of cleaning and equalizing the song. There can be large differences in sound quality, and sometimes the ideal version to use varies depending on the venue, time of night, or mood being conveyed. These multiple versions compound with the fact that files can use different compression algorithms and come in different bitrates. Thus, a tango DJ may have several versions of a single recording. In this way, the discography of 14 thousand tangos, milongas, and valses can turn into a library several times this size.

What About Tango Music Today?

The full history of tango music has led us to a very special moment today. Hugely important and influential tango music from artists such as Astor Piazzolla and Horacio Salgán, along with continued output of the greats from the Golden age, were made well into the 60s, 70s, and 80s. As a whole, however, the tango music industry experienced several decades of decline. The number of tango orchestras, number of recordings, and number of opportunities for artists dwindled. Fortunately for us though, dwindling is not the same as vanishing.

We are at the start of a new golden age of tango music. On my last trip to Buenos Aires, I was struck by the number of live orchestras you could hear, and by the quality of sound coming from all of them. A generation of tango musicians were able to learn from the greats of the golden age, who were able to pass along their knowledge before passing away. And that generation is teaching a new generation of musicians. The quality of technique, sound, and artistry of tango music today is incredible and is continuing to grow.

The advancements in recording technology throughout the decades allow us to listen to music from more than 100 years of tango. The hard work of restoring and remastering means these songs sound better than ever before. And the continued artistry and creativity of contemporary tango musicians means new tangos to enjoy listening to and dancing two are coming out every year. There is no better time to be a tango dancer and tango music listener than today.

____________________________________________________

References

[1] https://jens-ingo.all2all.org/archives/882, https://historyofrecordingblog.wordpress.com/24-2/

https://www.el-recodo.com/lostrecordings-en?lang=en

[1] Archived cylinder recordings can be found at the UC Santa Barbra library https://cylinders.library.ucsb.edu/.

[2] https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2010/oct/05/argentina-dance-tango-buenos-aires

[3] https://gearspace.com/board/mastering-forum/157797-please-we-need-help-form-experts.html

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/27/arts/27soun.html

[2] https://www.loc.gov/collections/emile-berliner/articles-and-essays/gramophone/

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/27/arts/27soun.html

[2] https://www.loc.gov/collections/emile-berliner/articles-and-essays/gramophone/

[3] Archived cylinder recordings can be found at the UC Santa Barbra library https://cylinders.library.ucsb.edu/.

[4] https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2010/oct/05/argentina-dance-tango-buenos-aires

[5] https://gearspace.com/board/mastering-forum/157797-please-we-need-help-form-experts.html

[6] https://www.el-recodo.com/lostrecordings-en?lang=en

[7] https://jens-ingo.all2all.org/archives/882, https://historyofrecordingblog.wordpress.com/24-2/

[8] https://www.todotango.com/english/history/chronicle/302/The-electric-recordings-and-a-marketing-trick/, https://www.tangomusicsecrets.co.uk/uncategorized/victor-electrical-1926/

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_radio

[10] https://youtu.be/Wbx7Pn87uGQ?si=tj3NPrYLzYXED-cC

[11] From the Discography of Francisco Canaro https://sites.google.com/site/franciscocanarodiscography

[12] https://www.todotango.com/english/history/chronicle/4/DArienzo-Tango-has-three-things/

[13] https://www.tango-dj.at/index.htm

[14] https://blogs.telosalliance.com/the-history-of-magnetic-recording-tape

[15] http://jens-ingo.all2all.org/archives/2776

[16] https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/rock-n-roll-and-military-dictatorships-almost-destroyed-argentine-tango

[17] https://humilitan.blogspot.com/2014/12/the-dark-ages-from-days-of-burned.html

[18] https://whyy.org/articles/encore-for-iconic-camden-recording-company-with-a-new-spin/

[19] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RCA_Records

[20] https://variety.com/2017/music/news/elvis-presley-archivist-ernst-jorgensen-interview-1202529943/

[21] http://www.totango.net/rca.html

[22] https://tangoteca.all2all.org/tango_sellos/index.html