I recently took a series of workshops with Jonathan and Clarisa. The Friday classes were a “Seminar on the Basics” while the Saturday and Sunday classes covered the more advanced topic of changes of dynamics. Something I found interesting was, while the Saturday and Sunday classes were completely booked, noticeably less people attended Friday. Talking with some people about this, they mentioned they thought a class focusing on basics was meant for more beginner dancers, so they waited to take the advanced seminars. Is a basics class a beginner class, or are they different? What are the different types of classes and who are they for? And what does class level mean?

Here is a taxonomy I developed which I find useful for both understanding the different types of classes and for when I design my own classes. Classes can be broken down into topics, where a topic denotes a move, technique point, musical concept, drill, or really any distinct component. Topics can be simple or complex, with complex topics being more challenging to do successfully. Classes can cover a few simple topics, many simple topics, a few complex topics, or many complex topics.

A back sacada is more complex than an ocho because there are more potential points of failure with a back sacada than with leading or following an ocho. But this does not mean one is easier than the other. What separates simple from complex topics is less the challenge on the high end and more of the chance of failure on the low end. We can make even the simplest step very challenging by adding enough detail. In fact, perhaps the most impressive thing someone can do in tango is a simple movement with exquisite detail. The fidelity that each topic is covered is another dimension of classes. Walking may be as simple as putting one foot in front of the other (low fidelity). It can also be very high fidelity with posture, connection, muscles, joint mechanics, and timing. Thus, we have a taxonomy of eight potential types of classes, as shown in the table below.

| Low Fidelity | High Fidelity | |

| Few simple topics | Beginner Class | Fundamentals Class |

| Many simple topics | Intermediate Class | X |

| Few complex topics | X | Advanced Class |

| Many complex topics | Master Class | X |

Beginner classes cover the basics, going over a few simple topics in light detail to give new dancers a chance for success. Fundamentals classes similarly covers basics but do so in high fidelity. Beginner classes are not fundamentals classes and fundamentals are not just for beginners. Unfortunately, tango commonly combines beginner and fundamentals classes, leading to new dancers feeling overwhelmed and more experienced dancers having critical gaps in their knowledge base.

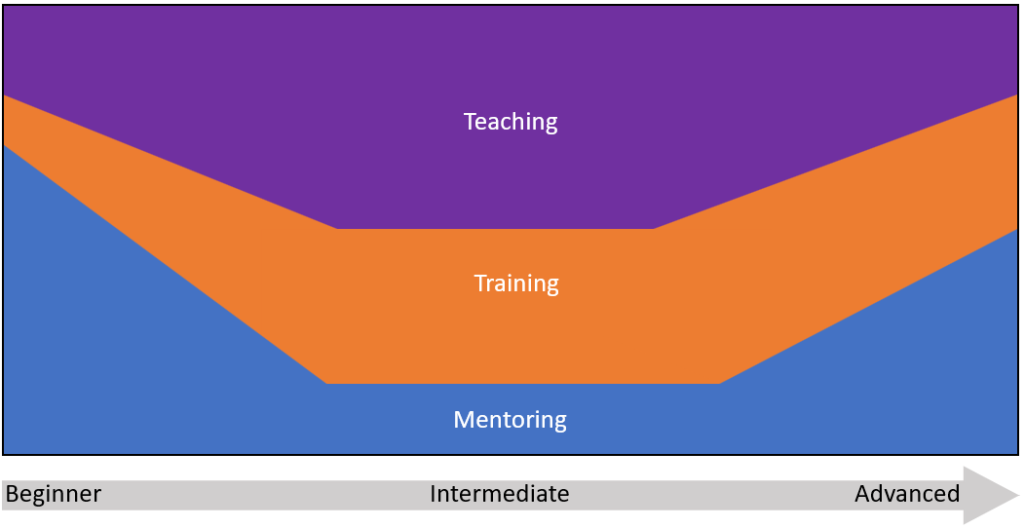

Intermediate classes teach how to string sequences together and layer topics such as navigation and musicality to the movements. The challenge comes not from the individual steps or details, more from the combination of factors. Advanced classes actually cover less topics but cover more difficult topics in more detail. Master classes combine complex topics to show new possibilities, highlight areas for improvement, and help break out of old patterns. The different classes serve different purposes, and the level of a class does not coincide with the level of dancer that should take the class. Someone dancing for less than a year can get a lot of benefit from an intermediate or advanced class, and fundamentals classes are valuable at all stages of development.

So, what do the big X marks in the table represent? In the movie The Prince’s Bride, the protagonist is imprisoned in ‘The Pit of Despair’, a torture chamber where his lifeforce is slowly sucked away. This seems a rather fitting description of a bad tango class. The three X’s mark tango class pits of despair to be avoided at all cost.

We have two guides which indicate where the pits of despair lie. The first is the ratio of walking to talking. Take the class time spent doing divided by the class time where the teacher is talking. If the walking-to-talking ratio is below one, there is a good chance the class is falling into a pit of despair. The second guide is the success ratio, which is the number of times students succeed divided by the number of times they. A low success ratio leads to frustration and scares students away from the topic.

Classes are like maps in that there is a limited amount of information which can be presented. You can’t show a large area in detail on a map; nor can you teach many topics in high fidelity. If you try, then you end up talking more than doing and you end up torturing more than teaching. Complex topics also need sufficient detail for a decent success ratio. You can gloss over a lot of the nuances of a sidestep and still have beginner dancers successfully lead and follow one. Gloss over the details while teaching leader ganchos and your students are in for a different experience. Master classes can get away with teaching complex topics in low fidelity because they assume the students already have some level of mastery of the individual elements.

Something interesting about the Jonathan and Clarissa workshops was that the Friday class on the basics ended up being the most useful. As we can now see, they were not beginner classes, but fundamentals classes, which laid the structure for the rest of the weekend.