Our body is our instrument, and our movements its song. Musicians have the language of notes and scales, but what language should we use as dancers? Improvement requires a target to aim for and a precise description of what we are trying to do. The ways to describe tango technique are as varied as the dancers themselves. “Be light but grounded,” “engage your core,” “use your lats,” “soften your knees,” and “just relax” are all common cues given to tangueros. All cues can be useful, but the tango student is inundated with a barrage of differing and sometimes conflicting feedback. We need a clear framework to understand and describe movements.

I have found it transformational in my understanding and teaching to analyze movement by what the joints of the body are doing. Using joints as the basis of analysis offers several benefits. First, it is concise. While there are hundreds of muscles, there are only a few key joints. Second, it is universal. The understanding of “be light but grounded” varies by person, but “point your foot” always describes the same movement. Finally, joint movements are externally visible. We may not know what a performer is thinking or feeling, but we can see their joints move. This essay provides a framework for the lower body and how it moves, while a follow-on essay describes the upper body.

I make several simplifications, such as omitting some joints and defaulting to layman’s terms instead of using technical terms (I include the technical terms in parentheses for those interested). I also use dance terminology, which has some differences from anatomical terminology.[1] At the same time, I will do my best to provide information that is clear, concise, and correct.

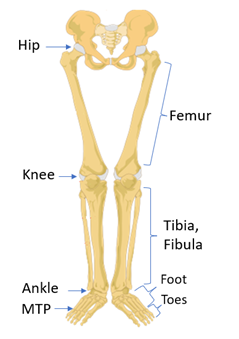

A joint is where two bones connect. There are four joints in the lower body for us tango dancers to consider: the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint connects the toes and foot, the ankle connects the foot and lower leg (tibia and fibula), the knee connects the lower leg and upper leg (femur), and the hip connects the upper leg and and pelvis. A Free leg means it is not weight bearing and a standing leg means is bearing weight. We describe movement at the ankle or MTP joint by the bone directly below it, so pointing the foot is movement at the ankle joint and flexing the toes is movement at the MTP joint.

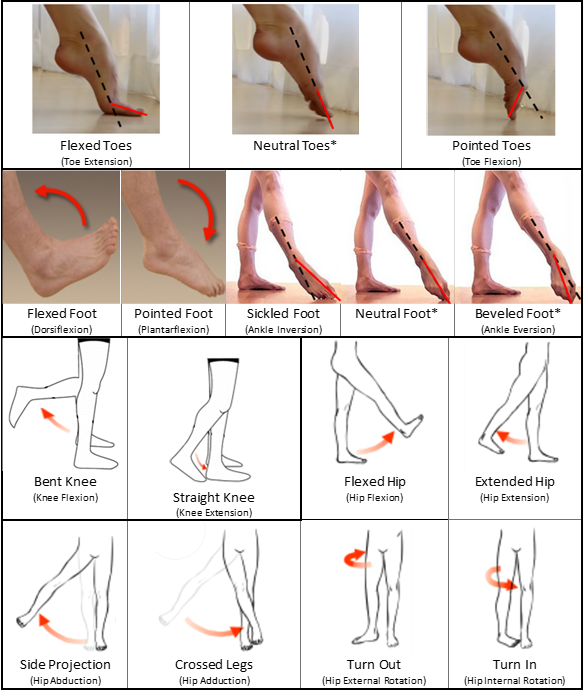

The toes point and flex; the foot points, flexes, sickles (inverts), and bevels (everts); the knee bends (flexes) and straightens (extends); and the hip can flex, extend, turn in (internally rotate), turn out (externally rotate), and can project the leg side (abduction) and cross the leg (adduction). This list contains the lower body movements we need to know as tango dancers, and the table below shows each movement and gives its technical term in parentheses.

The value of this framework comes from being able to identify and describe movements, so it is worth taking some time to solidify your understanding. I suggest you try the following exercises:

- Isolate each of the joint movements in your own body. I.e., move one joint at a time.

- Slow down[2] and watch https://youtu.be/ujs4hFT2Kz0?t=23 from 23-40 seconds. Pick one dancer and describe their sequence of joint movements in as much detail as possible.

Applications to Tango

Now that we have developed a common framework of communication, we can discuss technical points with more clarity.

In tango, a beveled free foot is often considered desirable, and sickling is something to avoid. For stability, and to avoid an ankle injury, we keep the ankle of the standing leg neutral. Hence, a simple rule to follow for prettier tango feet is to bevel the free foot and maintain a neutral standing foot.

We get thrown off balance when the free hip hikes up, which can occur when our body tries to make room for the free leg to pass underneath us. If you are struggling with balance on a move, a simple cue is to flex the free hip and knee to fold your leg underneath yourself. This allows space for your leg to collect while maintaining a level pelvis, leading to better balance.

Working on walking backwards? Try the cues of triple extension and triple flexion. On the back projection, extend your free hip, knee, and foot (triple extension) to create a nice line and space for your partner. Then, on the transfer of weight, flex your hip, knee, and foot (triple flexion) to control the landing.

Turning in or out at the standing hip causes us to lose stability[3], whereas turning in or out in the free hip allows for freedom of movement. A simple rule that is helpful for more complex movements such as gonchos is: stability in the standing hip, mobility in the free hip.

Having control over our movements is critical to effectively using our instrument. Of course, knowing is not the same as doing, and we must practice to learn new concepts. But a clear and precise language leads to clear and precise understanding. It gives us a clear target to aim for.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

- Anatomical terminology describes movements based on moving towards and away from the fetal position. Dance terminology instead uses words that attempt to convey an image of the desired movement. For example, pointing toes in dance actually refers to toe flexion in anatomical terms. ↑

- You can slow a YouTube video by clicking the gear icon in the lower-right corner and selecting playback speed. ↑

- Having some turn out at the standing hip can be desirable, we just don’t want to change the hip position after we shift weight onto the leg (we want to maintain whatever turnout we start with). ↑

1 Comment

David Phillips · January 22, 2023 at 8:11 pm

Bravo—a wonderful example of clarity in thinking, writing, and presentation.

This echoes what sports coaches and clicker-trainers have learned. Elite athletes can recognize the feeling and respond to internal cues, such as “float the top while grounding the bottom.” But most of us better recognize and respond to external, observable cues. Succinct, focused cues, like those you give for the extension and collection phases of a step, also have important benefits.

Comments are closed.