Written by Sean Ericson and Jacqueline Pham

Your teacher presents a sequence at the start of class, and even though they repeat the sequence several times, you struggle to remember all the steps and end up lost. While you may eventually get the sequence, your partners miss out on the practice opportunities while you struggle to remember. You also spend the whole class time figuring out the steps and miss the deeper lessons the teachers are trying to impart. It takes you a while to memorize the movements, but in no time, you forget the moves, going back to your same tried and true steps when you get to the milonga. Maybe the information you struggled to learn and then forgot will make sense one day, but probably not. More likely it will end up in the same void as so many other classes you took. We believe this describes the experience of most people during a class. It doesn’t have to be this way.

It is not the fault of the information, the class structure, or the instructors who put a lot of time and thought into how best to present the material. It is also likely not the fault of your memory, your abilities, or your desire to learn. Instead, the culprit is that you do not have a system to prepare for and process the information you receive. You don’t have a way to quickly memorize the sequence, so you spend the class trying to remember instead of learning. Here we lay out a method for being able to quickly understand and remember tango sequences.

Being able to remember steps and sequences is a valuable skill for any tango dancer, leader or follower, performer or social dancer. Of course, it is valuable for making the most out of classes and workshops. But understanding how sequences are constructed also helps when it comes time to develop your own sequences. Knowing how movements fit together is essential for improvisation, and being able to quickly understand sequences empowers followers to fully embody their dance and add their own voice (including embellishents).

The trick to quickly memorizing sequences is to have a mental checklist that helps you remember the steps. Instead of watching the sequence and then afterwards asking “What did they do?”, you want to have a set of questions you ask before the teachers show the sequence and try to answer the questions as the sequence is being shown. Here we discuss a mental checklist we use which enables us to (usually) remember a sequence by the second to fourth time we see it and to ask better questions in order to understand the sequence. If you struggle to remember steps, we recommend trying out this process.

When you are presented with a sequence, try to answer the following questions:

- With which foot/feet do the leader and follower take their first step?

- What is the entrance?

- What is the exit?

- What are the nuggets of the sequence?

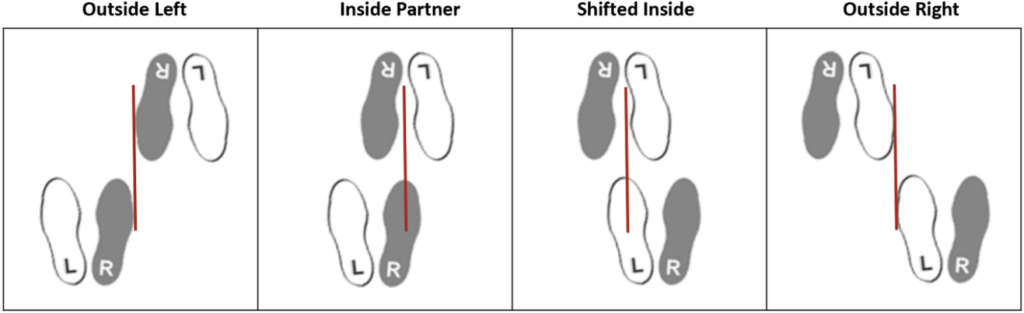

The first question is a simple one, but if we don’t ask it then we will figuratively and literally start off on the wrong foot. Don’t wait until you see the sequence before trying to answer with which foot you begin stepping. You can often answer it before the sequence even begins, saving time and mental space for the other questions. One trick we sometimes use is to think in terms of the open and closed sides of the embrace rather than left and right. We find it can be challenging to quickly identify yours and your partner’s left and right feet (especially given your partner’s feet are flipped relative to yours) whereas we tend to be able to quickly identify the closed side and open side of the embrace.

Teachers construct a sequence around one or two ‘nuggets’ they find interesting and then add an entrance and exit to get in and out of the interesting parts. This helps us to quickly deconstruct and remember the sequence. Instead of seeing a long string of moves, look for a beginning (entrance), a middle (the nugget) and an end (the exit). The first time you see a sequence it can be helpful to focus on the entrance and exit, and then focus on the nuggets of the sequence the subsequent times you see it. Teachers also tend to use the same entrances and exits (probably half of class movements start with 1-2 of the basic and end with 6-7-8). Instead of trying to remember each step, see if you can map it to an entrance and exit you already know.

Once you identify the entrance and exit, you then identify the interesting nuggets of the sequence. This will be the interesting, unique, and often more difficult part of the sequence. Here are two tricks to help remember the nugget of the sequence. The first is to break the nugget into packets of two to three steps. We are already doing this by splitting off the entrance and exit, but it can be applied to the middle portion of the step for a longer sequence. The second is to relate these packets to a similar move you already know and focus on the interesting twist you don’t know. The more you can relate to moves you already know and identify the new and unique elements, the easier it is to remember the sequence. As a simple example of how these tips help, see how quickly you can memorize the sequence “wdelhlolrol.” Then, following the steps of packeting the sequence and relating to things we already know, note how the sequence “hello world” can be memorized almost instantaneously even though it is of the same length and uses the same letters.

Putting this process into action, imagine you are a beginner learning the basic eight for the first time. It is a challenge to memorize eight different steps, and even harder to also focus on the technique pointers your instructors and partners are giving you. Going through our checklist: (1) The first step is with the closed side of the embrace (right for leaders, left for followers). (2) We can think of the entrance as back, side, forward (for leaders, mirrored for followers). (3) The exit is forward, side, collect (for leaders, mirrored for followers). (4) The nugget of the move is stepping to the cross. Instead of 8 things to memorize, you have three pieces: the 1-2-3 entrance, the 4-5 cross, and the 6-7-8 exit. I have found this breakdown into the beginning, middle, and end makes it easier for beginners to remember the basic eight.

The approach presented here is only one of many approaches, and you are encouraged to find what works best for you. The important part is to have a process for remembering the steps, which in turn helps you ask better questions about the nuggets. Waiting until the teacher shows the move to see if you can remember is a recipe for failure. Instead, have a plan for success and practice that plan. That way you will be able to spend less time remembering and more time learning, less time thinking and more time creating, and less time memorizing and more time dancing.