What should we look for in an instructor? And as an instructor, what do we need to provide our students to support their growth? Categorizing instruction into the three roles of teacher, trainer, and mentor is useful for answering these questions. A teacher conveys information, getting the student to understand something they did not know before. A trainer helps get information into the student’s body, getting the student to be able to do something they could not do before. And a mentor shows the student a path forward and supports their feelings and emotions along their journey.

A teacher is responsible for the knowledge component of learning. Teachers give us information on what to do and how to do it. Go to a class and most of your interaction with the instructor will be them teaching you information. The mark of a good teacher is that their students have a good mental model of what we need to do to become a better dancer. Learning consists of both knowing what to do and being able to do it. Teachers deal with the knowledge component and are therefore necessary but not sufficient for learning.

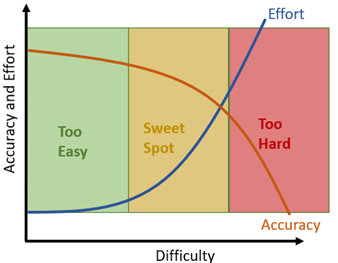

A Trainer helps convert knowledge in our head into understanding in our whole body. Training tends to involve less talking and more doing, using a few well-designed drills and well-chosen words to build competency. As a trainer, it is better to say one thing a hundred times than to say a hundred things once, and sometimes the best is to get the point across without saying anything at all. A trainer’s job is to boil down the information given by the teacher into small packets that the student can focus on. The teacher shows the student what they are trying to do, the trainer gives them feedback on when they need to put their focus to achieve this and when they are progressing in the right direction.

A Mentor plays a more infrequent but equally vital role in a student’s development. The job of a mentor is to ensure the components for growth are in place and remove barriers to learning. While the teacher and trainer take care of the student’s day to day growth, a mentor gives broader guidance and encouragement throughout their journey. Broadly speaking, trainers focus on what to do in the next minute, teachers focus on what to do in the next week, and mentors focus on what to do in the next year. Suggesting teachers to study with, guidance on how to structure practice, and pointing the student in the right direction of music to listen to and performers to watch all fall under mentoring.

Mentors help the student process their feelings and emotions; something especially important for newer dancers. Experienced dancers, inoculated to the social dance experience, can easily forget the raw emotions that come with your first dance event. Finding the courage to ask someone to dance. Processing when your cabeceo is not returned. Understanding your emotions when you are not asked to dance for several tandas or when you are thanked after one song. Having support when someone acts inappropriately at the milonga. Strategies for having a positive experience at a festival or marathon. Navigating partner dynamics. Finding a healthy balance between the desire to dance and the needs of other aspects of life. All these moments are the job of a mentor to help the student navigate. Having support during these moments makes the difference between the student becoming a lifelong dancer where tango enriches their life, and the student experiencing emotional damage and finding another hobby.

The three roles of teacher, trainer, and mentor can be played by different people, but can also be played by the same person. As a student, it is helpful to know what role we are looking for in an instructor at a given time, and as an instructor it is useful to know what role will be most helpful to the student in each moment. I believe that knowing which role to play is one of the most important skills of an instructor, more important even than knowing what information to share or how to structure a class.

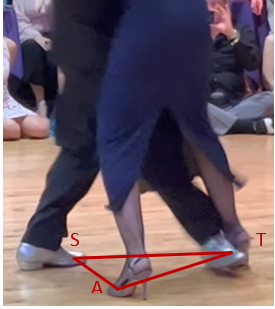

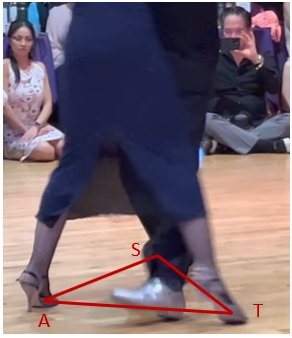

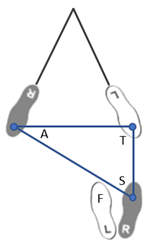

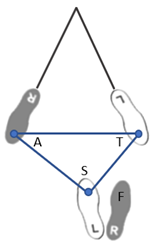

Say we are working with a student on their forward walk. We may start in teacher mode, discussing and demonstrating the physics concept of equal and opposite reaction to explain how, to go forward, we use our standing leg to push the floor backwards. We summarize with the phrase “drive the floor backwards to step forward.” Once the student has a clear path forward then we go into trainer mode and practice the concept, using the cue ‘drive’ to connect with this concept. We have the student practice with several different movements, giving short corrections and words of encouragement. At the end of practice, we may switch into mentor mode and show the student how to approach filming themselves so that they can practice their walk on their own. The power of separating roles is that it provides clear guidance on the amount and type of information to provide. We can say a single word such as ‘drive’ while the student is in motion, whereas it would make little sense to try and explain Newtonian physics in the middle of a movement. Similarly, repeating a single word would be of little help without the previously teaching what that word refers to.

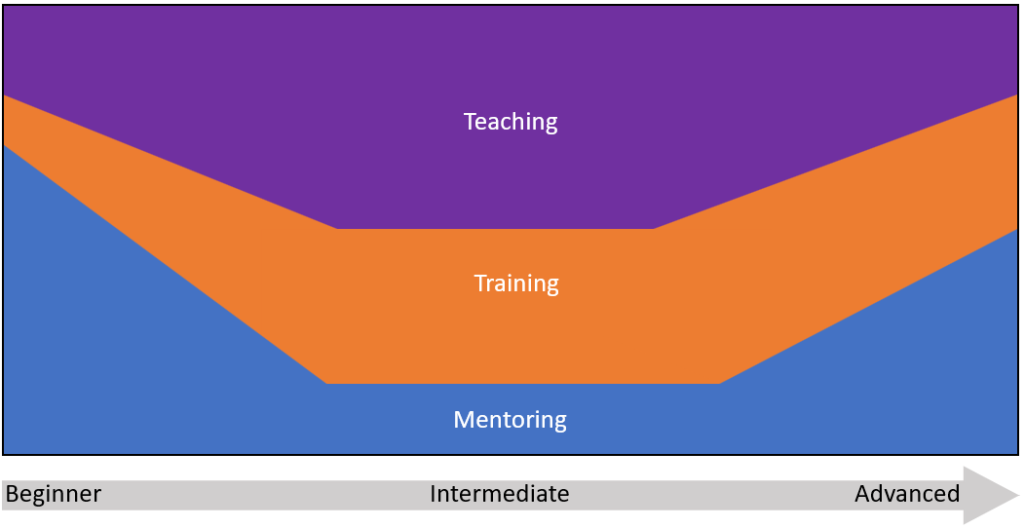

The instructor categories help us understand how the needs of the student change as they progress. Beginner students primarily need mentors to process their new experiences, which is why what makes a good beginner instructor is often different from what makes a good instructor for intermediate or advanced dancers. As the student grows, teaching and training take center stage. Advanced dancers often require less teaching and more training. Advanced dancers also need more mentoring to help them choose where to focus their attention.

Separating the different roles helps us avoid some common instructor pitfalls. One common pitfall as a teacher is to expect immediate change in our students. Teaching is like planting seeds, where the flowers of understanding may blossom weeks or months after the learning is planted. When inevitably information does not produce immediate change, we give more information and more information, overloading our students and hindering their progress. Worse, we may blame our students, thinking that they are lazy or “they just don’t get it.” Once we separate teacher from trainer, and mentor, we allow for separation from the information we give as a teacher and the progress that comes through training. We also allow separation from the information and the broader structure that enables learning.