A “yummy embrace” is practically synonymous with a desirable tango dancer. But when it comes to understanding how the embrace works, we are at a loss for words. Maybe this is because of the words we use. We tell dancers to “connect with your chest,” “relax your shoulders,” “disassociate,” and all manner of other cues, often without them having a clear idea of what these cues mean. A lack of clarity in communication leads to a lack of clarity in understanding, and the embrace stays a mystery. Let’s see if we can shine some light on the topic in the next few pages.

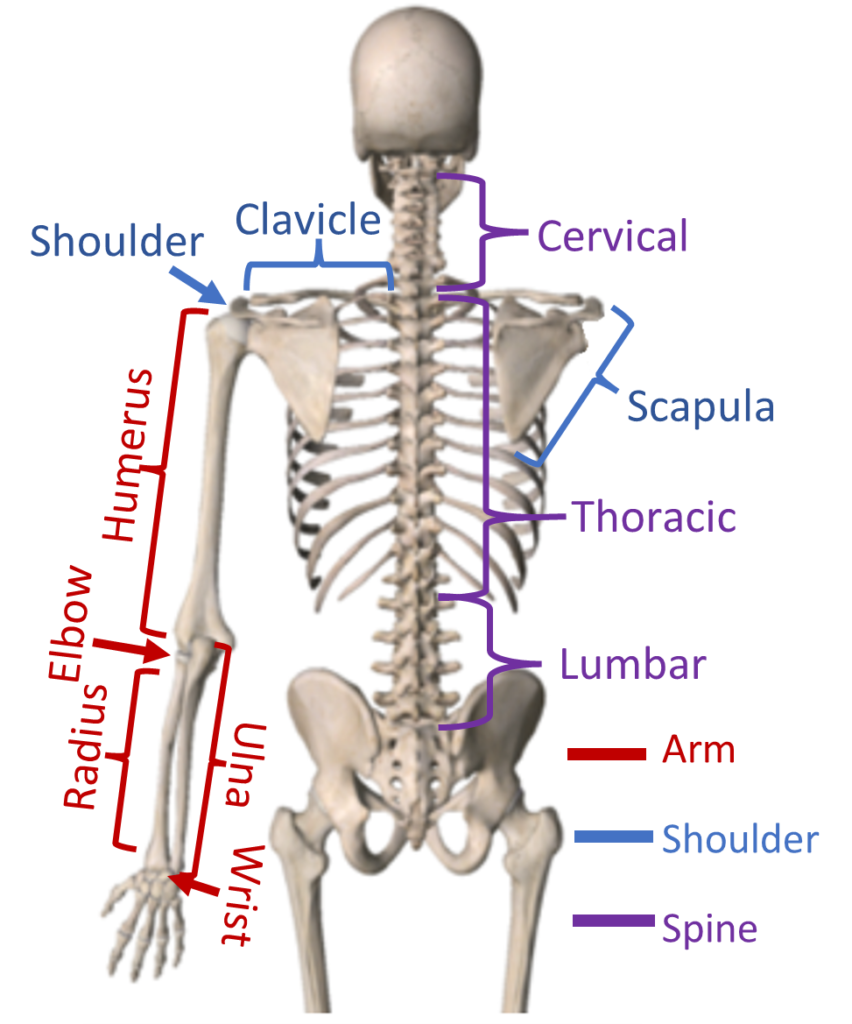

The upper body has a lot going on, and there is no way to cover it all in a few pages. Luckily, we are allowed some simplifications, and a little knowledge goes a long way for our purposes. The upper body can be broken into three components: the spine, the shoulder complex, and the arm. The spine includes the lower back (lumbar), upper back (thoracic), and the neck (cervical).[1] Because the ribs and breastbone (sternum) move with the spine, they can be thought of as part of the upper back. The shoulder complex consists of the shoulder blade (scapula) and collar bone (clavicle), which form the shoulder joint. The upper arm (humerus) and lower arm are joined by the elbow, and the two bones of the lower arm (ulna and radius) form the wrist.

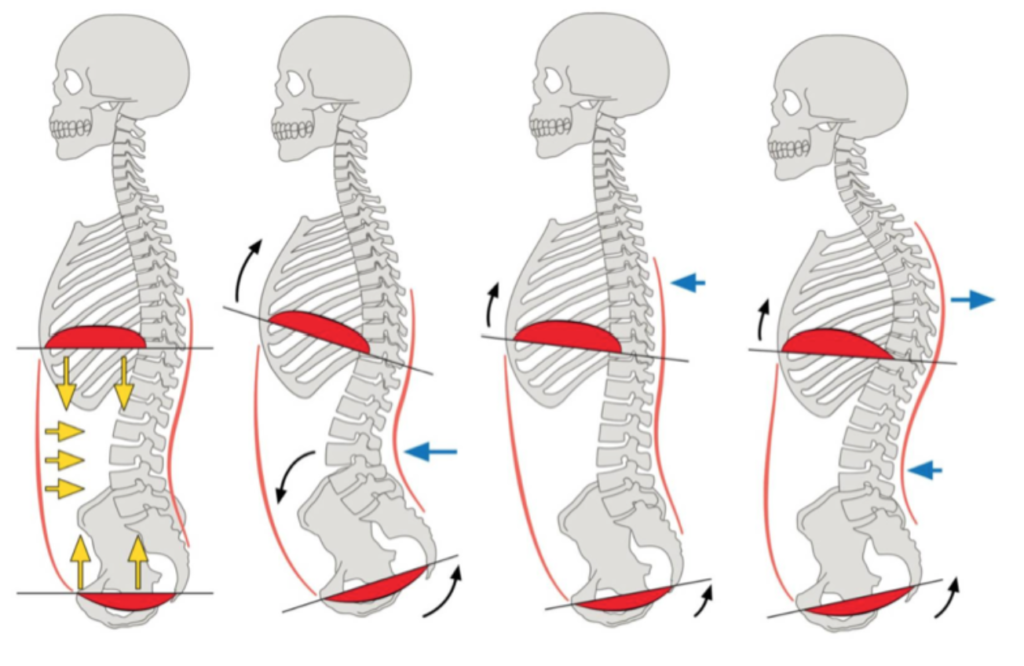

The spine can bend forward (flexion), backwards (extension), sideways (lateral flexion), and can rotate. Social tango primarily utilizes spinal rotation, though corrections often are for other spinal movements. For example, the feedback to “stand up straight”, often means you currently have too much flexion in the upper back.[2] The neck can rotate more than 80 degrees, and a flexible upper back can rotate around 30 to 40 degrees as well. The lower back is not really designed for rotation, and too much rotation in the lower back can throw off our posture and lead to lower back pain. When rotating with the spine, we want to find the movement in our upper back and in our neck, not in the lower back. A rule that applies to spinal movement in general is to strive for more movement in the upper back and more support in the lower back.

How to Rotate

Tango dancers are told to “lead with your chest,” and “keep your chest facing your partner.” But the breastbone is limited in how much it can rotate. You cannot reach a position of hips perpendicular to your partner’s with spinal rotation alone, much less the rotation required for movements such as back sacadas. While some dancers solve this problem by simply forgoing movements that require much

rotation, a fuller understanding of body mechanics allows us to both stay connected to our partner and have freedom of movement.

Our shoulder blades can raise and lower (elevate and depress), can spread apart and pinch together (abduct and adduct), and can rotate outwards and inwards. Try each of these movements to get acquainted with how your shoulder blades move (tip: scapular rotation occurs whenever you raise your arm overhead).

Sliding our shoulder blades on our back changes the position of our shoulder, which in turn changes the position of our embrace. We can rotate our embrace by spreading one shoulder blade and pinching the other. To create more rotation, use your shoulder blades. Control of your shoulder blades gives you both freedom of movement and quality of connection.

Maintaining contact with your partner does not mean you need to be breastbone to breastbone. Our bodies are three dimensional, and we can connect with the sides of our body just as well as the front. In fact, the contact point should slide for many movements and indicates properly working shoulder blade mechanics. Also, while a close embrace is beautiful, don’t confuse contact with connection.[3] Open up a little if need be. You can be connected in an open embrace and can be chest to chest but totally disconnected from your partner.

We can move the arm within the shoulder joint and can move the whole shoulder, and we use both at different moments in the dance. Phrases such as “disassociate” can be useful shorthand once we understand the correct mechanics but are insufficient for describing the complex relation between spine, shoulder, and arm. Understanding when to create space by rotating the spine, by moving the shoulder blade, and by moving the arm in the shoulder joint goes a long way to achieving the nice embrace we are all seeking.

Embrace Mechanics

The arm can swing forwards (flexion), backwards (extension), sideways (abduction), and across our body (adduction). It can also rotate in the shoulder joint (internal and external rotation). Move your arms out to the side and bend the elbow so that the palm is facing the floor and the elbow and hand are both parallel to the floor. External rotation causes your hands to be higher than your elbows (so your arms and head make a W position), and internal rotation causes your hands to be lower than your elbows. The elbow can bend (flex) and straighten (extend), and the wrist can flex, extend, and bend sideways (radial and ulnar deviation). The wrist can also rotate with the thumbs turning inwards (pronation) and outwards (supination. Remember, the way you rotate your wrist when eating soup is soup-ination 😉 ).

There is a list of 5 things to consider when positioning the arm: (1) side extension, (2) forward extension, (3) elbow bend, (4) shoulder rotation, (5) wrist rotation.

As seen in the photo of Magdalena and German,[4] the following joint positions constitute the mechanics of the open side of the embrace.

1. Extend arm sideways (abduct)

2. Bend elbow

3. Externally rotate arm

4. Rotate wrist

We do not need forward extension in the arm of the open side of the embrace, though some dancers may find a bit of forward extension more comfortable.

For the closed side of the embrace, the leader extends the arm forwards, bends the elbow, and rotates the wrist to face the partner’s back. It is also common to rotate slightly internally, so that the hand is either parallel to the elbow or slightly below the elbow. The arm can be directly forwards (elbow in same line as shoulder) or can be a bit to the side (elbow outside of shoulder) depending on the embrace and the needs of the movement.[5]

The closed side of the embrace for the follower can be a bit more complicated because the follower’s arm is on top of the leader’s, so the specific joint mechanics will depend on the relative heights of the partner. The followers embrace can also change depending on close embrace versus open embrace. Unfortunately, I am not a sufficiently knowledgeable follower to know all the variations, but the five choices of amount of side extension, forward extension, elbow bend, shoulder rotation, and wrist rotation still apply.

Troubleshooting

The embrace can be particularly challenging to troubleshoot. Here are a few tips to help.

Start low and work upwards, start inwards and work out. The spine affects our shoulder blade, our shoulder blade affects our arm, our arm affects our hand, and our hand affects our partner. If we have a slouched posture and bad shoulder position, then putting the arm in the proper position relative to our body will feel incorrect relative to our partner. First start with the joints lower and towards our midline, then work upwards and outwards.

One joint at a time. Trying to fix too much at once will lead you to tense up. Instead, gain control and understanding of one joint. Once you have found control and found the correct position, then you can move on to the next joint.

Rotate the shoulder blades around, not up. A common embrace mistake is to elevate the shoulder blade, while another common mistake is to not let it slide around our back. We want movement, just movement in the way we want.

Externally rotate the open side arm. If your arm comes forwards and your partner corrects you by moving your arm back, it is very likely that you forgot to externally rotate. Try moving your arm back to the same position, but with external rotation, and see if it feels better to your partner.

[1] While the sacrum and coccyx are part of the anatomical spine, from the dance perspective it is best to include them with the pelvis.

[2] Avoid over-extending the lower back in an attempt to “stand up straight”. A good cue is that if the bottom of the ribcage is opening, then you have over-extended the lower back.

[3] This advice, passed along to me at a workshop, has always stuck with me, though I unfortunately cannot remember who the instructor was and so cannot give proper credit.

[4] Image adapted from https://www.genovatoday.it/eventi/workshop-lezioni-show-tango.html

[5] The arm can also come across the body (adduct) when your partner is on the left side of your body.