Milo of Croton was an ancient Greek wrestler with a novel approach to training. As the legend goes, to train for the Olympic games, Milo took a small calf and carried it to the top of a hill near his house each morning. As the calf grew bigger, Milo grew stronger to meet the greater challenge. By the end of the process, Milo had unlocked beast mode and could carry the fully grown bull up the hill. With his newfound strength, Milo went on to win gold at the Olympics. Let us apply some of this ancient Greek wisdom to our own tango journey.

What are the components of Milo’s training protocol which lead to his success? Milo sets a goal—win the Olympic gold in wrestling. To achieve his goal, he gathers his resources—a hill near his home. He chooses a training frequency—once per day. And finally, he chooses a difficulty—weight of bull. Milo uses a process called progressive overload, where you incrementally increase the difficulty of a task to build a staircase from where you are to where you want to be (see here for additional discussion on this idea). The same process of progressive training can be applied to our tango.

We first decide where we want to go before we can get there. I suggest you take a moment to write down a couple of goals you want to work towards. Goals can be specific or abstract, and it can be good to have a combination of both. Here are some examples of goals I have had: develop a comfortable embrace, do well at a competition, finish a choreography for an upcoming performance, expand my vocabulary of steps, develop better posture, make clearer from the outside the musicality I hear inside, make my lead clearer from inside the couple and harder to see from outside the couple.

Having the right resources is critical to your progress. A tree grows when it has the right mix of soil, water, and sunlight. Our dancing is no different. Progress is the result of having the resources we need, and stagnation is simply a symptom of missing resources. The most crucial resources to tango growth are: (1) teacher, (2) partner, (3) practice space, (4) colleagues to collaborate with. Take a moment to check if you have each of these resources available. The fastest growth tends to happen when we have all four. But there are many ways to adapt if we are missing one component, we just need to be strategic. Say you don’t have a partner, probably the most common missing component for tango dancers. Instead of putting your progress on hold until the perfect partner magically falls into your embrace, be proactive. You can get with a group of friends to work together and work through concepts and drills together. It may be easier to find two or three people to work with occasionally than one person to exclusively partner with. This way you can fill the space of a partner in aggregate. There are many ways to effectively work with limited resources if you take stock of what you have and what you need.

How much do we need to dance to get better? Obviously if we have too low of a frequency then we won’t improve, but do we have to train every day like Milo? Tango dancers tell stories about their marathon practice sessions, and tend to exaggerate the training schedules of professionals, (e.g., “I hear they practice seven hours every day.” ) What we need to remember, though, is that not all tango time is the same (see here for more discussion of this idea). I have seen dancers go to the milonga every night and a marathon every weekend, but only actually practice an hour or two each month. You don’t need much time to get a lot of growth, you just need to be consistent and set aside time for actual practice.

Shifting the analogy for a moment, practice sessions are like houses in Monopoly. Any number of houses are better than none, and more houses pay more dividends, but the benefit of each additional home is not the same. The third home always gives the most incremental benefits. Similarly, any number of practice sessions is better than none, and more practice tends to give more benefits, but three practice sessions per week tends to give you the most benefits per hour spent. Less than three per week and your body starts to forget what it learned between sessions. More than three is nice, but additional sessions tend to have lower incremental benefits. So, see if you can sustain three before trying to add more. Each session does not have to be that long. Your schedule could be as simple as meeting with a partner once for 90 minutes on day 1, doing solo exercises for 30 minutes on day 2, and committing to focused practice for the first hour of a practica on day 3. You would then have gotten your three days a week of practice in just three hours.

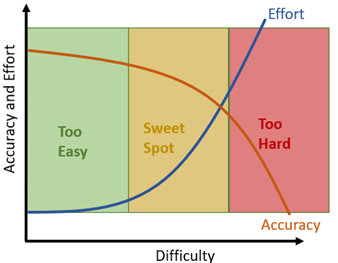

Difficulty is a variable we progressively increase (see here for ways to change difficulty). Bringing the analogy back to Milo, try and pick up a bull right away and you’ll get crushed, keep lifting the calf forever and you won’t grow. So, what is the right level of difficulty, and how do we find it? Effort and accuracy are both functions of difficulty and are our guides to dialing in the right level of difficulty. Effort is the mental and physical exertion we feel, and accuracy is our success rate and precision. Effort increases with difficulty and accuracy decreases with difficulty.

High accuracy with low effort means the difficulty is too low. We call this this hanging out in the green zone, where everything is safe, and learning doesn’t happen. Low accuracy and high effort means the difficulty is too high. We call this the red zone, where you are overwhelmed, and you develop bad habits. The area of high effort to maintain high accuracy is the gold zone, the sweet spot of optimal difficulty where progress occurs. When you practice, you always want to find your gold zone. You know you have found it when what you are practicing feels challenging yet doable.

| Difficulty | Effort | Accuracy |

| Too Easy – Green Zone | -Feel bored -Task feels automatic | -Miss because not paying attention -Always get it right |

| Lower End of Gold Zone | -Comfortably focused -Like a fun, interesting game | -Usually correct -Occasional error |

| Upper End of Gold Zone | -Fully concentrated -Hard challenge | -Both successes and failures -Struggle to get it right -Know cause of misses |

| Too Hard – Red Zone | -Overwhelmed -Drinking from a fire hose -Feeling of confusion | -Miss and don’t know why -Feels like luck when you get it right |

As you progress, your green zone expands, and the gold and red zones shift. You then need to progressively increase the difficulty to stay in the gold zone. You need a bigger bull to keep the same challenge. You have to keep challenging yourself. Training is about being able to do tomorrow what you can’t do today. If you just keep repeating what you could do yesterday, then you are not really training and should not expect to improve.

The life cycle of the stereotypical tango dancer starts in the red zone, feeling overwhelmed with all the information. The ones who stick around then find a moment of the gold zone where progression happens quickly. (This usually occurs a little earlier for followers, but tends to last a little longer for leaders, which is why we often say followers learn faster early on, but learning is harder for more advanced followers). Eventually the dancer gets to a place where their dance feels comfortable to them, and they start to hang out in the green zone. At this point they no longer have a stimulus to promote progress, and their dance remains constant, if not slowly declining, for however long they continue in tango. If not addressed, then the gold zone also starts to shrink, locking in their current state. Usually this is due to a combination of frustration—”I’ve been dancing for 20 years, why can’t I do this?”—and arrogance—”I’ve been dancing for 20 years, and I’ve never needed that.”

Though common, this process is completely avoidable. We can find continuous and joyous growth for as long as we dance. Find some goals worth working towards. Marshall your resources and plan around your constraints. Set aside some time each week to practice. Find the joy in challenging yourself and pushing yourself to be able to do something tomorrow that you can’t do today. Little by little, and step by step, you will find your dance transform in a truly positive way.