When I was two years into my tango journey, I attended a workshop with a couple whose dancing I admired. At the end of the classes I was lucky enough to dance with the instructor. Afterwards she said my was coming along well and asked if I was open to a piece of feedback? Of course, I wanted to hear! She said, “Remember to make a triangle for your sacadas.” The whole ride home I was repeating to myself remember to make a triangle for sacadas, remember to make a triangle for sacadas. When I got home, the question finally came to me: but what kind of triangle?

I majored in mathematics, so I have a knack for overcomplicating everything, and for thinking way too much about triangles. Are sacadas the symmetric beauty of equilateral triangles? Or maybe the right answer lies with Pythagoras? A sacada is a cute step, so should I think of acute triangles? Or wait, scalene and sacadas both start with ‘s’ and have seven letters. that must be the answer. I believe I finally have an answer, which I share with you here.

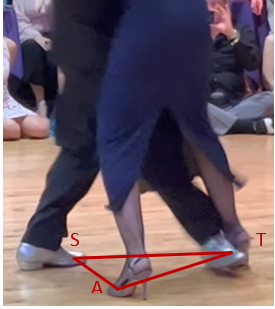

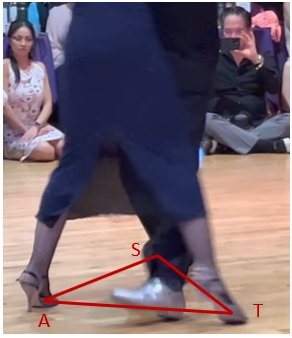

A bit of vocabulary. The term sacada is comes from the Spanish word sacar, which means to take out.[1] Our standing leg is the one we have weight on and our free leg does not have weight. We step onto the arriving leg, and step from the trailing leg. A sacada is when our arriving leg intersects our partner’s trailing leg. In this way, we generate the effect of “taking out” our partner’s leg. There are three points: the foot of standing leg which will be our trailing leg when we step (S), the foot of our partner’s trailing leg (T), and the foot of our partner’s arriving leg (A). These three points form a triangle.

Our arriving leg intersects our partner’s trailing leg somewhere between the ankle and knee. The figures below show a sacada towards the ankle (where there is no gap between the intersecting feet), and a sacada towards the knee (where there is a gap between the intersecting feet). All photos are taken from a performance of Gustavo Naveira and Giselle Ann in Austin Texas (https://youtu.be/Ez8y8iS8qPQ).

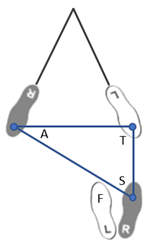

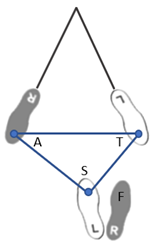

The game of sacadas is all about where we position our standing leg. We position our standing leg (S) such that our free leg can step in a straight line to intersect our partner’s trailing leg without having to cross our own feet. What makes this game challenging is that our feet and our hips have width. This is not a problem when our free foot is inside the base of the triangle but presents a challenge when our free foot is outside. Doing a back pivot compounds the problem, because it generally moves the free foot farther outside the base of the triangle.

Here is my diagram to highlight the idea. Our partner takes a sidestep from their left trailing leg to their right arriving leg. If our standing leg is on the right, then our left foot (F) lies inside. This is the most forgiving sacada as most triangles work. A right triangle even works well here (first figure). Now suppose we are standing on our left foot, so our right free leg lies outside the base of the triangle. This is less forgiving, as a right triangle would make us cross our feet. Because of the width of our feet, we need to shift the vertex of our standing position to be more like an equilateral triangle. Finally, say we are standing on our right foot and want to do a back sacada. Then we need to shift over the standing leg vertex even more because the hip has width, and the back pivot moves our foot outside of the base of the triangle.

A great game is to have your partner pause with feet apart. Play with how the position of your standing food needs to shift to comfortably complete the three sacada positions shown in the diagrams. You need to shift your standing foot when your other foot is in the outside position and shift even more to when the back pivot moves it to the outside position. Another great game is to do the same sacadas but do it in the sidestep after the forward in the turn. The 90° degree turn between the forward and side step changes the geometry. Take a few minutes to play these games, they are well worth the time.

The figures below show an interesting example of this principle. In the first figure, Gielle’s standing foot is close to Gustavo’s arrival foot to accommodate space for her back pivot. In the second figure, Gustavo also does a back sacada, but his pivot brings his free foot inside the base of the triangle, so Gustavo’s standing leg position is closer to Giselle’s trailing leg.

Sacadas work or fail based on where the standing leg is positioned. Where the standing leg is located depends on where you last stepped. Thus, a sacada will work or fail, will feel comfortable or uncomfortable, based on the step before. You could spend forever troubleshooting a step without any progress, because it is the step before that matters. My final answer is that there is not one kind of triangle. You move the standing foot to make space for your foot width and for your hip pivot. Now go find the triangle for each kind of sacada you want to make.

Nota Bene from Jacqueline Pham

Similar to Sean, I think of sacadas in terms of triangles. We have the same map, but I invite you to consider an additional angle of the sacada triangle.

The partner receiving the sacada will typically move horizontally across the trajectory of the partner entering the sacada. Thus, the Trailing and Arriving legs of the receiving partner are the same as the above diagrams. However, I tend to think of the remaining leg of the triangle (which belongs to the partner entering the sacada) as the FREE leg (F) rather than the standing leg.

Notice that in each of the 3 sacada triangles above, the free leg forms a right triangle as it enters the sacada near the Trailing leg (the 90-degree vertex of the right triangle). Sometimes this trigonometry can shift, but aiming for this right triangle using the Free leg helps me find the sweet spot, regardless of whether I am leading or following, entering or receiving the sacada.

As a leader: if I am entering or receiving the sacada and my partner’s trajectory is too close or too far away from me, then I can adjust my standing leg however necessary to have my Free leg form a right triangle as it enters the sacada.

As a follower: if my partner’s trajectory is a bit askew or if they do not pivot me enough, I can use the goal of achieving a right triangle to either A) turbo-charge my pivot before the sacada to get my Free leg into the right trajectory, or B) understand that I will have to enter at a more challenging angle and turbo-charge my pivot after the sacada/upon arrival to compensate and correct the trajectory. I use the same right triangle principle for both entering and receiving a sacada to chart out the ideal setup and resolution. Consider this the Drive Assist that I, as the driver of our tango vehicle, can engage in case of unexpected road conditions to turbo-charge our dance.

[1] In high school Spanish class, we had to memorize the phrase “sacar la basura” which means “to take out the trash.” That and how to ask for directions to the library are pretty much the sum total of what I learned in my years of high school Spanish.