During a conversation with some fellow dancers, my friend Mitra Martin said something which I believe gets at the heart of the learning and teaching process. She said, “The job of a teacher is not to teach, but to create an environment where learning occurs.” Passing along information through instruction is a vital part of learning, but it is only one part of the broader learning environment. Even the best instruction will fall on deaf ears if the learning environment does not allow knowledge to be translated into skills. How do we create effective learning environments in tango?

We can look to other dance forms for inspiration. When I first started dancing, I was fortunate to try many different dance styles and see how each created the learning environments. At one end of the spectrum lies ballet classes, which leverage uniformity to promote learning. Everyone in class does the same movements, and many of the exercises repeat from class to class. This allows everyone to apply the same feedback given by the instructor, and information can be layered across classes to build proficiency. At the opposite end of the spectrum is breakdancing, which leverages individuality. Everyone discovers their unique style and then can share their discoveries with each other and ask for feedback, fostering a culture of collaboration. Dance forms such as ballroom, salsa, or modern dance also have their own approaches to creating learning environments. Each approach has its benefits and requirements to be effective.

At its best, the tango approach to learning combines positive aspects from several different styles. We have classes and seminars to provide a structured progression like ballet classes but can also have sharing and discussion during prácticas like in breakdancing. We have lessons and partner practice like in ballroom, along with the community support and learning like in other social dances. Of course, this is tango at its best. Unfortunately, it is too often the case that the tango learning environment ends up being an ineffective combination of seminars without structure, prácticas without practice, and community without communication.

Consider the pre-milonga class. The community spends good money on good instructors, but the instructors come in without knowledge about the number and level of students, and the students have no control over the difficulty of the class. Instructors often change week to week, meaning the teaching approach can vary dramatically, the feedback can be contradictory, and errors of understanding or retention go uncorrected. If that were not enough, the students do not even have time to practice the material they learn before going directly into the milonga. Festival classes often face these same challenges but also have the added factors of larger classes and sleep deprivation.

Organizers are balancing many aspects of tango that, such as making an event social, showcasing art and artistry, creating an event people come to, and making an event which is profitable and sustainable. It is little wonder that the learning environment occasionally gets neglected. We can’t put the full burden of creating effective learning environments on the organizers and instructors. It is the responsibility of the entire community to create and maintain healthy learning environments.

So, what are some steps a community can take to create better learning environments? It helps to first realize that there are actually multiple spaces that need to be created and coordinated to create an effective learning environment. Learning progresses fastest when there is a good balance between learning, practicing, and doing.[1] In general, practice spaces get the least attention. The simple addition of open floor times and guided prácticas can make a big difference by providing a space for actual practice to occur. At a festival, for example, replacing one of the Sunday class slots with a guided practice would probably be the most valuable use of the teachers’ and participants’ time and energy, because it would give everyone the chance to try out all the new material they have learned over the weekend and correct mistakes while they are still fresh. If, as a community, we value open floor space and guided practices and are willing to pay for them instead of just paying for the flashy classes and workshops, then I am sure organizers would be more than willing to provide such spaces. The different spaces do not need to be part of the same event or held at the same time. A big, generally missed, opportunity for learning comes after a community hosts a workshop or festival. If the community organizes review time in the subsequent weeks for participants to go over, practice, and discuss what they learned, maybe even with the guidance of local instructors, then it can substantially increase the level of retention and understanding. It is the maestros who hold the workshop, but it is the full community that holdsds together the structures that allow learning from the workshop to occur.

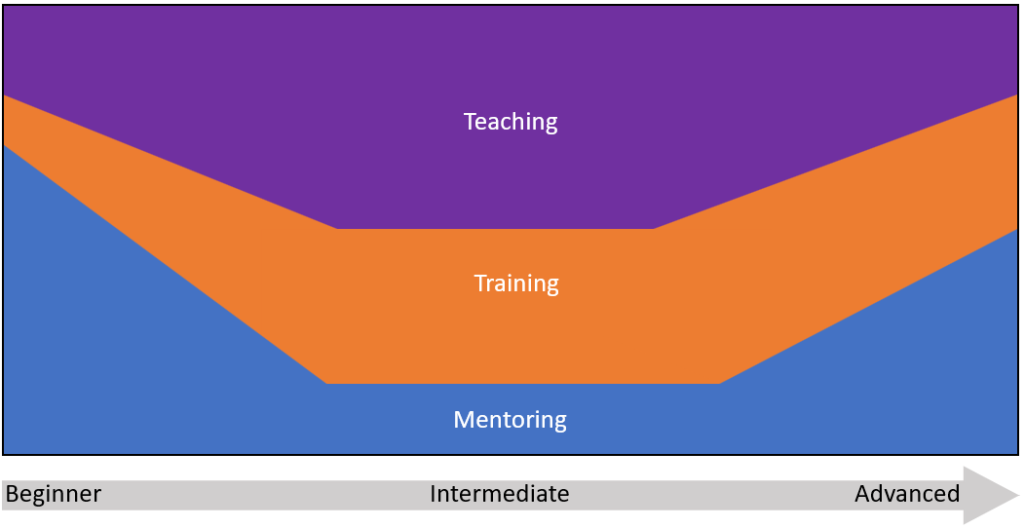

Another important factor to remember is that the needs of a novice are different from the needs of an advanced dancer.[2] Ideally, different environments can be created to address the needs of dancers at different levels. Novice dancers learn well from structured, progressive classes from a consistent instructor whereas intermediate dancers often benefit from being exposed to many different concepts, teachers, and styles. The needs again shift when students transition to an advanced level where they require more mentorship along with goals to continue developing their skills. Opportunities to teach (or assist teaching) and perform are essential for advanced dancers to support their continued growth. At all levels, it is helpful to have a cohort of fellow dancers with whom to train and collaborate.

A final consideration is that not all spaces need to be learning spaces. We sometimes jam learning into places where it would be better to simply focus on connection and enjoyment. Instead of holding a pre-milonga class just because “it is what has always been done,” a community could instead have a pre-milonga cocktail hour to create a space for people to connect socially before the dancing begins.[3] Clear distinctions between learning spaces and enjoyment spaces allow for more focus when it is time to learn, and more fun when it is time to enjoy.

[1] You can read more of my thoughts on the topic of the various types of spaces here: https://tangotopics.org/prepare-your-tango-kitchen/

[2] You can read more of my thoughts on how training needs vary with level here: https://tangotopics.org/teacher-trainer-mentor/

[3] Shoutout to the organizers have started doing creative events such as having a potluck, or wine and cheese tasting before the milonga.